BBC Radio correspondet

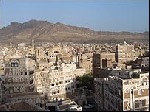

BBC Radio correspondet - Sitting high up in the rocky mountains of northern Yemen, the country's capital Sana’a is finding that its dwindling water supply may not be able to sustain the ancient settlement.

I had almost walked right past the low doorway in the souk before I realised.

Then I stopped, peered into the gloom, and spotted it - a camel, sporting leather blinkers the size of small searchlights, circling the chamber, a wooden arm linking it to a central stone pillar which rotated as the animal tramped stolidly on.

It was a simple mill for producing sesame oil - and it would hardly have looked out of place at the time of Christ.

Arabia Felix

If you want local colour, then go to Sana’a. The entire old city is a Unesco World Heritage Site, complete with tall stuccoed houses whose perforated walls use the winds for natural ventilation.

There is the small square which covers the site of the 6th-Century Christian cathedral, though nothing now remains of its ebony and ivory pulpit or its crosses of silver and gold.

In the narrow lanes of the market you are pressed to buy a bag of dull golden crystals and your senses succumb to the smell of burning incense. To the Romans, Yemen was, after all, Arabia Felix, the home of frankincense and myrrh. They still make novel souvenirs.

Venture further, beyond the Old City's 30-foot-high (9-metre-high) clay walls, and there are plenty more reminders that Sana’a is one of a kind. There is the Military Museum, an eclectic assembly of old weapons (including a camel-mounted cannon), old motor cars, and relics of the British colony in Aden.

A chillingly topical touch is an illustration from the 1950s of an execution, the bloodied scimitar still in the swordsman's hand as the convict expires. Perhaps that explains why the museum is run by part of the interior ministry - the moral guidance department.

Sana’a is at least 2,500 years old. It claims to be the world's oldest inhabited city, though Damascus disputes that. But it is living on borrowed time.

For once climate change is not the presumed culprit. It is not natural causes at all - it is human behaviour.

Qat crop

However you do the sums, they just do not add up. There are nearly 20 million Yemenis - and the population doubles every 17 years.

The country imports most of its food, largely because it has too little water to feed itself. Yemenis have about one-fiftieth as much water per head as the world average.

And, to confound confusion, insupportably large amounts of water go on a non-essential crop - qat.

Qat in today's Yemen is what smoking was in Britain a generation ago. Everywhere you go you find men with cheeks bulging bizarrely as they get their fix. It is a shrub whose leaves, when you chew them, can induce mild euphoria, excitement, hallucinations and even constipation.

It is increasingly popular in Yemen. While a few years ago men would spend a couple of hours a day on their habit, many now chew happily away for seven or eight hours.

Within the last five years or so qat use has become much more accepted among women. One young professional woman told me she chewed it perhaps once every three months, as a way of socialising.

More often, she said, would be too much. She blames the drug for what she says is Yemenis' failure to better themselves.

Moralising apart, qat is having a baleful effect on Yemen. Of the country's scarce water, 40% goes on irrigating qat - and qat cultivation is increasing by 10% to 15% a year.

You cannot blame the farmers. As one says, growing qat earns him 20 times as much as growing potatoes.

You probably should not blame the chewers either. In a country where almost half the people live on less than US$2 (£1) a day, you find your fun where you can.

Relocation plans

The minister for water and the environment is an agricultural engineer - and he is a worried man.

"The Sana’a basin is using water 10 times faster than Nature is replenishing it," he told me.

"And before long there won't even be enough to drink. I am not an optimist. I think many of the city's people will simply have to move away.

The minister, himself a chewer, thinks weaning Yemenis off qat will be like breaking the tobacco habit.

"In time it won't be cool to chew," he says. "But time is what we don't have."

One of the ancient Arabic names of Sana’a translates as The Protected City. It looks as though the protection is running out.

From Our Own Correspondent was broadcast on Saturday, 7 April, 2007 at 1130 BST on BBC Radio 4.